February 2007

![]()

Essays, poems, opinions and humor on seeking

and finding answers to your deepest life-questions

|

This month's contents:

Douglas Harding in Memoriam | Is My Hair on Fire Yet? by Shawn Nevins | Songs of Kabir | Solitary Spiritual Retreat by Bob Fergeson | Progression by Art Ticknor | On Faith and Accord with the Way by Hubert Benoit | Humor > Sign up for e-mail alerts that will let you know when new issues are published. > Want to meet some of the Forum authors in person? Interested in meeting other Forum readers? Watch for more information on the meeting schedule and programs. The next TAT meeting will be held on the weekend of April 13-15, 2007. > View video clips of the TAT spring conference DVDs: "Beyond Mind, Beyond Death" and "What Is Spiritual Action?" |

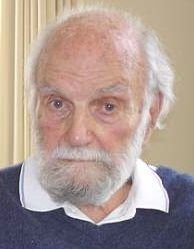

In Memoriam: Douglas E. Harding

February 12, 1909 - January 11, 2007

Douglas Harding had the voice of a Shakespearean actor, the intellect of a scientist, the imagination of an artist, the heart of a buddha. To know him was to love him.

When we first met a couple years ago he greeted me (as I'm sure he did everyone) as if we were long lost kinsmen—and as we shook hands I indeed felt I'd somehow always known him. The occasion was "The Gathering," an annual Harding workshop in Salisbury, England. He was 95 years of age and mostly confined to a wheelchair, but he spoke with the passion and energy of a young man, expounding ideas he'd been teaching for 60 years as if they were being verbalized for the first time.

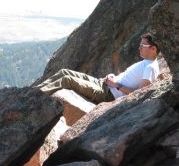

Douglas Harding, 2005

Douglas Harding, 2005

An excellent writer, Harding had probably a dozen books published in his lifetime, including the comprehensive, Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth, which C.S. Lewis called a "work of genius." The book that first got him noticed, however, was On Having No Head, in which, among other things, he describes his own Awakening experience as being characterized by the realization that he, quite literally, had no head.

What Harding experienced was the clear emptiness of no-self witnessed by all the great teachers—Buddha, Jesus, Maharshi, Nisargadatta… but his unique way of describing it to himself and others was to say that one has "no head." This perception shaped his teaching and evolved into a series of what he called "experiments" one could do to experience "headlessness" for oneself. These experiments, and Harding's tireless efforts to teach them to as many people as possible, constitute a legacy of immeasurable worth.

In essence, Harding's teachings and experiments ask us to simply look "what is" square in the eye and report honestly what we "see"—to become a completely scientific, objective witness to what is on display. Looking out on the world, can I see my head? What, if anything, exists "behind" my head? If there is no head here, what and where am I? And so on. Honest, scientific reporting of what's true for you—right now!—at "first person central."

An interesting aspect of Harding's teaching of headlessness is that it can be experienced on more than one level. After reading Harding and earnestly trying the experiments, many, if not most people come to an intellectual understanding of headlessness—an acceptance of its inescapable logic, its irrefutable self-evidence. This may happen gradually, or as a sudden epiphany. Some people are affected so strongly they incorporate this new way of "seeing" into their philosophy and actions, and find that this awareness of headlessness has an immensely beneficial effect in their daily lives.

There is also what might be called a "visceral" experience of headlessness, characterized by a sudden, startling shift from being somewhere (here, behind these eyes) to being nowhere—or rather, to being everywhere at once. The first time this happens one might feel a bit like Wylie Coyote as he realizes he's just chased the roadrunner out over an abyss. As exhilarating as it is to be floating free, one can't help but feel one really should be getting back.

And then there is the final realization of "no-self" described by all the great teachers, which might also be called "permanent headlessness." Harding's great contribution is to have given us a tangible methodology for looking directly into the realm of no-self—right now, without further worthiness or preparation—and start to make friends with it.

I've written before how moved I was by his words as we parted, when he called me, as I'm sure he did everyone, "my dear, dear friend." I treasure every moment of my short time with him. By whatever measure of greatness one uses, Douglas Harding was a truly great man and my debt to him is beyond calculation. Rest in peace "little Douglas." Rest in peace, my dear, dear friend. —Bart Marshall

![]()

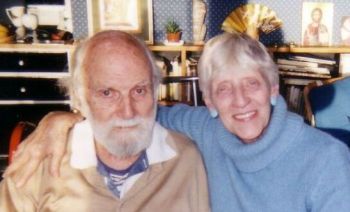

Douglas and Catherine were kind enough to invite me into their home—well, to be more accurate, to agree to my request to visit them—when I was a stranger from another country wanting to bypass one of their public workshops and spend time one-to-one with Douglas.

I spent several hours (six if my memory isn't exaggerating the turmoil) driving a rented car from Ipswich, England to their home, which was only about twelve miles out from the city. What threw me for a loop were the traffic circles, which I had to approach on the "wrong" side of the road, driving a car with a steering wheel on the "wrong" side and a manual gearshift lever on the "wrong" side. By the time I shot through a few of those circles, I had no sense of compass direction. And I saw many sights over and over before finally locating the B&B a mile down the road from the Hardings' residence. Once there, I parked the car and refused to take another chance on getting lost. The next morning the B&B owner drove back to the rental agency in Ipswich with me following, and I got rid of the car.

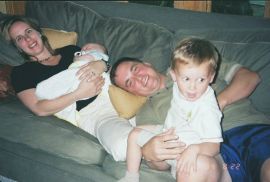

Douglas & Catherine Harding, 2003

Douglas & Catherine Harding, 2003

On the way back, shortly before lunch, he dropped me off for my first visit with the Hardings. Catherine greeted me warmly at the door of a contemporary-style home that had been designed by Douglas, who had been an architect by profession. Douglas was sitting in a wheelchair in his living room—this was in October 2003, when he was 94, and while he was still ambulatory, he often used a wheelchair for ease of moving around the house. His first words after we shook hands were: "Your job is not to be Douglas Harding or someone else. Your job is to become yourself—your real self."

I spent the rest of that day well into the evening with the Hardings and returned the following day late in the morning. Sometime that afternoon I overheard Douglas, down the hall from the living room, say to Catherine: "He's like one of the family. It feels like we've always known him." I had been thinking along the same lines. It was as if we had become family—or closer than family in the way that sometimes happens in the family of seekers.

On the third and final day of my visit, which was a Sunday, Douglas had invited a few students to come for a mini-workshop. We did several of the experiments in direct seeing that he had developed over the decades, one of which was the tube experiment where two people put their faces in opposite ends of a paper tube while someone goes through a progression of questions on what's being seen from a first-person point of view. Douglas and I shared one of the tubes while he talked through the exercise for those of us present. While he was doing this, I saw very clearly that all objects of consciousness appeared on an internal viewing screen that was identical with what I look out from. This view opened a new perspective or paradigm of self and world that contradicted the paradigm I had been operating with for twenty-five years. I found that my mind could flip back and forth between these two contradictory paradigms and not be able to distinguish one as more true than the other.

The contradictory opposition of self being inside and things outside or vice versa had been oscillating back and forth in my mind for seven months when I went on a solitary retreat near Erie, PA in May 2004. During the retreat, Harding's tests for immortality (in his Little Book of Life and Death) brought my attention repeatedly back to looking at what I was looking out from. Those occurrences gradually brought me to the final faulty belief about the self, and then that was burned out by the truth of self-awareness.

Douglas provided the catalyst that completed my journey. Along with many others who received his beneficence, as long as memory lasts I'll be inexpressibly grateful for a wonderful friend. —Art Ticknor

![]()

Is My Hair on Fire Yet?

by Shawn Nevins

Part 1 of a transcription of Shawn's presentation at the April 2006 TAT conference, "What Is Spiritual Action?"

I'm going to start with a quiz, but there's only one question on the quiz and it's a multiple choice quiz. The answers… you've got three possibilities: answer A is, "on fire," answer B is, "lukewarm," and answer C is, "dead cold." Now, if you would, just close your eyes. The question is: How would you describe your spiritual search (or your spiritual path—however you want to phrase it)?

If you would answer A, on fire, please raise your hand right now … no peeking! [laughter] I won't name who peeked, but… Ok.

If you would answer B, lukewarm, raise your hand right now. Ok. And if you would answer C, dead cold, please raise your hand right now.

If you would answer A, on fire, please raise your hand right now … no peeking! [laughter] I won't name who peeked, but… Ok.

If you would answer B, lukewarm, raise your hand right now. Ok. And if you would answer C, dead cold, please raise your hand right now.

Alright, you can open your eyes.

I'm going to do a little bit like Mike [Gegenheimer] did, in that I'll start by reading what some other people had to say, and then I'll talk a little bit about my own experience.

I think the title of this talk was, how do I know that my hair is on fire? Is my hair on fire yet? Something like that. And it comes from an expression that, when I was in the Self Knowledge Symposium, we used to throw it around. That basically some Zen master long ago said that, "You should be searching as if your hair were on fire." And I tried to find the source of that, I couldn't find the source for it and sometimes it's phrased as "You should be sitting (or meditating) as if your hair were on fire." And the way that we took it is that it conjured up an image of someone who has a problem, an intense problem on their mind, and they're going to solve it, and that is sort of the "feel" that your spiritual search should have.

If you go through the literature, and I'll just quote a couple of famous folks right now, like Nisargadatta. He said:

How do you go about finding anything? By keeping your mind and heart in it. Interest, there must be and steady remembrance. To remember what needs to be remembered, is the secret of success. You come to it through earnestness.

When you are in dead earnest, you bend every incident, every second of your life to your purpose. You do not waste time and energy on other things. You are totally dedicated....

To know that you are a prisoner of your mind, that you live in an imaginary world of your own creation, is the dawn of wisdom. To want nothing of it, to be ready to abandon it entirely, is earnestness. Only such earnestness, born of true despair, will make you trust me.

Ramana Maharshi—some guy asked him: "When an endeavor is made to lead the right life and to concentrate thought on the Self, there is often a downfall and break. What is to be done?" Maharshi says: "It will come all right in the end. There is the steady impulse of your determination that sets you on your feet again after every downfall and breakdown. Gradually the obstacles are all overcome and your current becomes stronger. Everything comes right in the end. Steady determination is what is required."

Richard Rose: "Man must develop a system of work and work with persevering dynamism."

And even Douglas Harding, you know, the guy who has all these little exercises and experiments that seem quite humorous when you're doing them. I asked him, I said, "How do you stick with seeing?" And he said, "Determination, passion, and trusting."

So, back in the day, hearing all this kind of stuff I kind of summarized it here, the message that I got is that these are the things that it takes to succeed: Earnestness, Total Dedication, Determination, Dynamism, and Passion.... And I thought to myself, "Well, I don't really have any of those things." [laughter] "And that's a problem. I'm not like that at all. I'm not a determined or dynamic or passionate person, and I don't really pursue anything with earnestness. So I'm probably not going to get anywhere."

There's not—you know, in retrospect I look at this and I think, well, there's no great secret here: this is what everybody tells you—that to succeed in anything you've got to have these qualities. But in my experience, most people, myself certainly, most people that I know, don't have these qualities. And especially, those people like Mr. Rose, or Nisargadatta, we think that they had these qualities to the highest degree, and that there's no way that we'll ever live up to the type of person that they were, that they represent.

I say that—nowadays I say—that it's what we do when we are not inspired that determines our success. That it's what we do when we're lacking in all these things—that's actually what determines our success.

So now, a little bit about my story. There are three times that really come to mind when those qualities were completely absent, and when my hair was not on fire, and I was about as low as low can get. The first time was back when I was in the Self Knowledge Symposium. I was trying to figure out, well, am I going to move up and live on the farm here with Richard Rose, or am I going to stay down there and work with the group, work with Augie Turak and the folks down there? I could best summarize that as to say that the method there [the SKS] was to make yourself into a person of character—a strong and a willful person. And I pursued that. But at a certain point in time, you make progress and you make progress, then you plateau, and you level out, and you don't know what to do. And you keep doing the same thing again, and it gets depressing because you're not getting anywhere, and you just don't see a way out. The way out, fortunately, was to come up here, and to live on the farm, and to be around Richard Rose.

After a few years living up here, I was meditating as much as I possibly could, I was doing isolations, I was going to visit Mr. Rose—it was just tremendous inspiration. There was inspiration when I was in Raleigh from being around Augie Turak, there was inspiration when I was up here being around Richard Rose. And then, after a time, once again, it's like I plateaued and I felt like I wasn't getting anywhere. And Mr. Rose wasn't able to help me as much after a certain point in time because of the Alzheimer's disease. I pretty much didn't know what to do, again. I wound up going down to Florida, and I wound up just in the pit of despair down there in an empty house, by myself. I basically wasn't eating hardly anything, I wasn't exercising, and I wasn't meditating. And if it hadn't been for a few folks that I was calling on the telephone, I probably would have just thrown in the whole package, let's say.

But, I suppose that even when I was depressed, even when I thought that there wasn't hope, I was still going out, and I would go to the library, or I'd go to the bookstore. And I happened to find a little book by Douglas Harding when I was down there, and maybe that was just a little glimmer of hope. Anyway, I made it back up here, and I wound up going to the Linsly Outdoor Center. And while I was there, I started writing poems and started going out in nature, and sort of got re-inspired again and found a place within myself where inspiration came from.

Once again, after a period of time doing that—a couple years, let's say—I again got to that point of: I'm not getting anywhere, I don't know what to do next, I don't know what to read, there's nobody that can help me, none of my friends can help me, I'll just throw in the whole thing. I wound up going out to Texas … well, I'll go back a step, I actually wound up going to visit Douglas Harding, and there was a little glimmer of hope again.

I went out to Texas with the intention of starting a group. Started working on a web page out there—the spiritual teachers web page—and then finally something, let's say a breakthrough, happened for me. Something happened for me.

The short of it is: the picture of my search is just this wave of inspiration and depression, inspiration and depression, inspiration and depression. And I laid it out over a period of years and it almost looks like in retrospect it was like a three-year cycle of up and down, and up and down. But the cycle was weekly—that, you know, Monday might be things are going great and by Saturday, things are terrible, and I was just thinking—like I've said before—"If there was something else I could be doing, I would be doing it."

To me, that's just the way that the spiritual path is. I'm sure it's not that way for everybody, but from my experience, that is just the way that it is. In any one of those troughs, let's say, I could have made the decision that, well that's it, you know, I'm done with this stuff. And it might have been years before I got back to it; it might have been the end of my life before I got back to it.

I have the feeling that a lot of people who get into this, hit these periods, whether it's occurring on a weekly basis or a yearly basis, hit these periods and they don't see that they're going to come out on the other side of it and they stop, and they stop for a long time. And then when they get back to it, they can hardly remember why they started in the first place.

So, what are some practical things that you can do when you wind up in a place like this? And that's basically the point of this talk—is to say here are a few practical things that I think work and I think worked for me in my experience.

Now these [flips up flip chart paper to reveal a list of items] are not things that I invented by any means. A lot of them are things that Mr. Rose told us and that I just put in my own words, just because it's easier to remember that way.

Number 1 [item reads Find friends]: Just find friends. You know, I can't tell you the number of times that I was depressed and that all that it took was enough will power on my part to go talk to somebody, anybody, in my circle of the group and just have a conversation. You know, that is, if you want to call it the law of the ladder, if you want to call it the contractor's law, if you want to refer back to Mr. Rose's material. That's spelled out in there.

Number 2: Observe moods. Track them in your journal. I've said this before, if you're not keeping a journal, you're missing out on a major tool. And I add to that that you should periodically review your journal. I would literally go back and look at a whole year's worth of old entries and look through that and see what happened. At some point I know I went back and I reviewed them all. And this might be four years worth of journals. Now, as Heather said, I'm rather terse, so there wasn't a whole lot of stuff there. [laughter] For some people that could be volumes, but for me, it was do-able. But you know, it's something that—it takes some days to do.

But you see—you know, the whole thing that we're trying to do is just see ourselves, and when it's out on paper like that, to me it's so obvious

that, we're these little machines that are walking through an experience, and that machine had enough foresight to record some of that experience

for itself and now it can go back and look at it. And you know, and this is the thing, you've got to be able to project into the future that the same

stuff is going to happen again.

But you see—you know, the whole thing that we're trying to do is just see ourselves, and when it's out on paper like that, to me it's so obvious

that, we're these little machines that are walking through an experience, and that machine had enough foresight to record some of that experience

for itself and now it can go back and look at it. And you know, and this is the thing, you've got to be able to project into the future that the same

stuff is going to happen again.

Number 3: This is my own sort of little personal mantra—don't make big decisions in a negative mood. When you're in the dumps and it seems like nothing's going to happen for you and there's no hope, just:

Practice number 4: Wait. Okay. Just wait. And waiting is not a bad thing. In my mind I equated waiting with procrastination, and there's this very negative connotation with, well, you're just waiting, you're just killing time. Well, you're treading water in a sense until you're rescued. You can't swim right now because it's hopeless, but you can at least make the motions to tread water until something comes down the pike, and something will come down the pike if you learn to wait.

Is this hard? Yeah. I know how hard it is because the whole world looks a certain color and it looks like it will always be that way. And I can't tell you anything other than you just have to know yourself enough to know—have trust, let's say—that you'll come out of this, and you can look back on it.

Number 5 [Discriminate between waiting and the paralysis that comes from conflicting desires]: Tied in with learning to wait, is number 5, which is discriminating between waiting and the paralysis that comes from conflicting desires. Because we get stuck—sometimes we get stuck on the fence, and if we honestly look at why our path isn't going anywhere, it's because one half of us is thinking, you know, life is passing me by and my friends are all getting married, or, you know, they got a great job, and I should be doing that. And the other hour we're reading Nisargadatta and we're meditating. And that causes a certain sitting on the fence, let's say, or a paralysis, and that's different from this [pointing back at #4].

Number 6 [Know that inspiration will end. When it does, don't abandon your method. Keep pushing and looking]: Know that inspiration will end. Here's the thing, when it does, don't abandon whatever method you're using, whatever practice that you have. Keep pushing, but also keep looking. So, what I'm saying there, let's say your practice is effortless mediation. Say a person's got an effortless meditation practice, and you know, they're all fired up about it and they're doing it twice a day, twenty minutes a day, and they do that for six months, and then at month seven they do it, you know, just for one time twenty minutes a day, and at month eight, they're doing it every other day, and that kind of thing is happening. The inspiration has died away. When you see that happening, don't just go: "Oh well, ok, that's that, I've got to move on to something else." Keep pushing, because that's how you change what you are, let's say. That's how you become something other than a machine which is just ruled by its inspiration, or ruled by its moods.

At the same time, though, always keep looking. Like Rose said: be looking under every rock. Be working on your ways and means. What are the things that I'm going to be doing? What are new books that might catch my interest? What are different meditation techniques? Or, who are people that I want to go see? Those kind of things you should always be doing. Because, yeah, at a certain point, I think whatever practice you're doing, it is actually going to come to a dead end, and you will have to do something different, and hopefully you have explored enough things, you have enough books on your bookshelf, let's say, that you'll be able to go out and find something new and pursue that new route.

Number 7 [Be HONEST]: Last thing, and you know, it's two words… really this is everything: be honest. If you wanted to say what's the spiritual path, you could boil it down to those two words—just be honest. You know, if you were just honest with yourself, you wouldn't need any of this kind of stuff. You would be able to look yourself, as Bob would say, you would be able to look back—you'd be able to retraverse that ray, and you would know what's back there and you would accept that, let's say, or that knowledge would be allowed to come through.

Now, that's it. That's all I've got to talk about, because, you know, I don't like talking a whole lot. But, if there are things on there that you thought, "I don't know what in the world he's talking about when he said that," I'll be happy to explain it more, and we might find that this was a better talk for those questions than it would be if you were just listening to me.

Q: I don't think I know clearly what the difference is between waiting and the paralysis that comes from having conflicting desires.

Shawn: Yeah. On the one hand, you could say, "Well I always have conflicting desires, and I'll be cursed with conflicting desires until the day that I'm done with my spiritual search." You could say that, but there are times—and let me find an example from my life, and let's see if that will clarify it—there's a time, let's say, when I feel like, you know, "If I could find another person to share my life with, that that would bring me completeness. I think that that might be what I'm really looking for—it's just another person. Somebody to love," let's say. And, at the same time, a part of me says, "That person won't be there forever, I may die before that person, they may die before me, it may turn out that they don't like me at all. And this stuff that Mr. Rose is talking about, you know, finding who I really am, that's the most important thing."

So I sort of half-heartedly go about doing both of those things. And I wind up drilling myself into a spot where I'm really not doing either of those things, truly, I'm just sort of torn between those, and that's a point—to me, it's feeling paralyzed. I can't decide. Maybe that's what I'm trying to say, I just can't decide between these two things. As opposed to somebody who's decided that, you know, I will turn my head away from the pursuit of physical love, for a period of time, and I will devote myself to meditation. The mind, I think, just gets bored with things, it gets used to things and the novelty wears off, we wind up in a point where: "I just don't want to meditate anymore. It's not like I want to do something else instead, but I just don't want to sit for 30 minutes every day. I'm so sick of that, and it's not getting me anywhere anyway." And that's sort of a dead end. That's what I would describe as a point where I'm still going to keep doing that, but it's a feeling of waiting for something to come to me. I'm not going to make any violent effort to do something radical in my life. I'm going to wait for inspiration to resurface. I hope that made some sense.

Q: Are you defining waiting as a conscious behavior or attitude, and conflicting desires are more like an internal unconscious level?

Shawn: Well, I think if you're honest with yourself the conflicting desires are pretty conscious.

Same Questioner: So, they're both?

Shawn: I'd say that, yeah, they're both—if you are conscious, they're both pretty conscious, you know. But if you're kind of "sleepy" let's say…

Same Questioner: So we are procrastinating it too, because procrastinating might be unconscious—right?

Shawn: Well, again, I tend to want to give you the same answer… but, ok, yeah. Yes. We'll say yes. [laughter] For most folks they don't really realize that they're procrastinating. If you're doing this, learning to wait, you've reached a certain level of awareness, of yourself. That you're actually able to, perhaps, make the robot do something. [Gesturing up to the balcony] Of course we have no choice whatsoever, but… [laughter] But, damn it I'm doing to pretend like I do 'til the bitter end.

Bob Cergol: You can't do otherwise.

Shawn: Yeah, I can't do otherwise anyway. Anything else?

Dave Weimer: Where'd you come up with the "be honest" thing?

Shawn: The "be honest" thing… I mean, that's everything, you know—that's everything that—I mean that's all that… self-honesty.

Dave: …you might have heard of that concept or words before but…

Shawn: Yeah, I see what you're getting at.

Dave: …probably more profound that…

Shawn: Oh yeah. You know, it goes back to what Nisargadatta's saying, when he said—what does he say about when you're truly despairing? Basically he defines earnestness as true despair—that's when you're truly earnest—it's when you know how desperate your situation is. And that's when you have the capacity to be honest with yourself, is when you get an inkling of the route that life is going to take you if you don't do anything. Life has a certain plan in store for you—just physical life, let's say. And, you know, it all ends the same for everybody. It all ends in a big unknown. Just the thought that "If I could just," you know, everybody's saying the same damn thing all day today, "if I could just, in one moment, and the moment is right here, if I could just admit the nature of this thing, then I would know. And I can't. Because my whole identity is just wrapped up in being." And all that you want to do is live when it boils right down to it. All you want to do is be. And, you know, that's the thing—you want to be. You know, Doron wants to be. And we just—we can't fathom what is on the other side of that—that not being is okay.

But it wasn't for a long time, Dave, that I really—you know, people talk about giving up and that the spiritual path is—you know, that seems to be the most popular thing these days, is the idea that the spiritual path is the thing that's keeping you from achieving—the idea that I'm a spiritual seeker. And the problem, as we've said before, the problem with these teachings is that, yeah they're true, but they have to be true for you, in your experience. It can't be a thing that you read and then you shortcut through and you just say: "Oh, well, my spiritual path, that's the thing that's holding me up, and now I've given it up, so, now I must be enlightened." You actually have to come to the point where you don't care anymore about what you find, and you just want an answer. You just want to know something for certain. And it doesn't matter what that answer is, you just want to know something.

And that's a place that any of us can get to.

~ From a presentation given at the April 2006 TAT conference "What Is Spiritual Action?" Special thanks to Dan Garmat for the transcription. See the conference video page for DVD information. To be continued next month ...

![]()

Songs of Kabir

|

Solitary Spiritual Retreat

by Bob Fergeson

The practice of the solitary spiritual retreat, or isolation, is a method of self-discovery that has been practiced in one form or another

for centuries, from the monks in their quiet cells to the Tibetans in their secluded caves. In today's society with its hurried pace and

inescapable technology, this practice of spending time in silence and peace is even more important for those seeking contact with the

inner self. If, as Jesus once said, the Kingdom of Heaven is within, we would be well served to begin earnestly looking in that direction.

While books, teachers and the Internet can show us where others have gone before, and give us invaluable contacts, only we ourselves

can make the inward journey.

The practice of the solitary spiritual retreat, or isolation, is a method of self-discovery that has been practiced in one form or another

for centuries, from the monks in their quiet cells to the Tibetans in their secluded caves. In today's society with its hurried pace and

inescapable technology, this practice of spending time in silence and peace is even more important for those seeking contact with the

inner self. If, as Jesus once said, the Kingdom of Heaven is within, we would be well served to begin earnestly looking in that direction.

While books, teachers and the Internet can show us where others have gone before, and give us invaluable contacts, only we ourselves

can make the inward journey.

There are several pointers to help one in making time spent alone productive, and more than just a relaxing break from the pressures of daily life. The most important is to have a reason for your quest, to have a pressing question. Before I had come in contact with the technique of isolation, I intuitively knew that the best way to answer important questions was to go off alone, and find the answer myself, in myself. Later, after meeting others who had seen the value in this, the process was confirmed. This need not be only the big questions, such as "Who am I?" and "What is life all about?" but could also be about life's problems: "Why do I have difficulty with the people at work?" or "How did my marriage become so messed up?" or "Who are these people called my parents/kids?" The answers are found within, and can best be heard in quiet and silence.

I've heard it said that spending time alone is a cop-out, that it's simply a personality defense being taken as a spiritual endeavor, and this certainly can be the case, if it weren't for the question. Without a pressing question, and the focus required in bringing it to the forefront, time alone could be just a vacation from social pressure. I've seen this first hand, for my biggest problem in isolation was that I liked it, a lot. I would become very comfortable, and had to fight to keep the focus on the task at hand, and not drift into the pleasure of a tension-free environment. One way to keep this focus is to bring a few good books, ones that will keep our head in the right place. We can read a bit once in awhile to bring our head back to the problem and remind us of why we're there.

Another problem I've observed is that of fear. Some are afraid to leave society and its distractions, and thus cannot spend the time

alone necessary for the mind to relax and focus on inner questions. They might have problems they're avoiding, or place more value on

other's thinking than their own, and thus can't stay in the quiet long enough to produce results. One thing for certain, if you have one of

the above predilections, you will come face-to-face with it in isolation or retreat, and hopefully thus become more aware.

Another problem I've observed is that of fear. Some are afraid to leave society and its distractions, and thus cannot spend the time

alone necessary for the mind to relax and focus on inner questions. They might have problems they're avoiding, or place more value on

other's thinking than their own, and thus can't stay in the quiet long enough to produce results. One thing for certain, if you have one of

the above predilections, you will come face-to-face with it in isolation or retreat, and hopefully thus become more aware.

"The spiritual experiences that people have are a result of looking inside themselves." —Richard Rose

"Facing the unknown takes a lot of personal quiet and divorcement from the world around you. I studied this very carefully. It is the bridge between the inner and outer man. It takes hundreds of hours of facing the unknown to get the unknown to yield one little insight, one little piece at a time." —Jim Burns

We must also be comfortable. We need to spend our time in contemplation, not lost in the distraction of basic survival and fighting the elements. Moderation here is the key. While we do not want the distractions of cell phones and television, we also don't need to spend our time and energy trying to stay warm and dry, or fend off the the local wildlife and the curious. Too much frugality and we lose our time and energy, and so the same with too much distraction.

Fasting and celibacy are useful tools we can incorporate into our retreat, too. Fasting is a great way to shock the system and return to a quieter frame of mind, with less ritual, while abstinence saves our energy and helps turn our head away from the habitual draw of nature. If fasting has not been practiced before, it may be best to take it easy until you see how your system will react, and gain a bit of experience with it first. While fasting may be incorporated into the retreat to jumpstart the process and help restore our inner vitality, we shouldn't make asceticism itself the point. We're not going to get any deep thinking done, or clear our receptive mechanism in order to strengthen the intuition, if we are spending our time passed out under the desk. Moderation once more is key, especially until we become accustomed to fasting's effects.

|

If the brain and belly are burning clean ~ Exceprted from Fasting by Rumi, translated by Coleman Barks |

Most of the people I know that have practiced isolations have started out slowly, with perhaps three days and nights at first, then have gone on to retreats of three weeks or so two or more times a year. Whether it's for three days or a month, don't let temptation lead you into stopping early. Even if you're having trouble remembering why you planned the retreat in the first place, or feel it's no longer productive, sticking it out may have unseen benefits, even months later. Of course, there's no use staying if you're too ill or in real danger. The most difficult thing for me was to stay focused on the search and not be distracted by the beauty of the place and the slow passing of time. Staying focused was paramount.

Once you make the commitment to spend a block of time alone, don't forget to watch, to look at the various internal mechanisms before and during that will try to get you to postpone, leave early, or pass away the time in fantasy. If nothing else, you will have made the effort, and become more aware of yourself, and that's a good thing.

"Richard Rose gave me the best description of the attitude one should take. He said not to approach isolation as challenging God or the universe for an answer. Don't draw a circle in the sand and say you won't come out until you are enlightened. Instead, and this is my interpretation, work as hard as you can and be thankful for whatever happens." —Shawn Nevins

~ See Bob's web sites, The Mystic Missal, NostalgiaWest, and The Listening Attention.

![]()

Progression

by Art Ticknor

|

childhood being

|

|

|

self-conscious being

|

|

|

coexistent being

|

|

|

coexistent being

|

|

ego supreme |

|

|

|

ego diminishment

|

|

|

ego diminishment

|

|

doubting the self-belief |

|

|

meditating on the self |

|

|

|

||

Self-conscious Being

|

![]()

On Faith and Accord with the Way

by Hubert Benoit

According to Zen, man is of the nature of Buddha; he is perfect, nothing is lacking in him. But he does not realize this because

he is caught in the entanglements of his mental representations. Everything happens as though a screen were woven between

himself and Reality by his imaginative activity functioning in the dualistic mode....

According to Zen, man is of the nature of Buddha; he is perfect, nothing is lacking in him. But he does not realize this because

he is caught in the entanglements of his mental representations. Everything happens as though a screen were woven between

himself and Reality by his imaginative activity functioning in the dualistic mode....

Man ... does not know that there is in him something invisible which works in his favor in the dark. Identifying himself ... with his imaginative mind, he does not think that he is anything more. Everything happens as though he said to himself: "Who would work for me except myself?" And not seeing in himself any other self than his imaginative mind and the sentiments and actions which depend on it, he turns to this mind to rid himself of distress. When one only sees a single means of salvation, one believes in it because necessarily one wishes to believe in it.

However, if I look at the life of my body I observe that all kinds of marvelous operations are performed spontaneously in it without the concourse of that which I call "me." My body is maintained by processes whose ingenious complexity surpasses all imagination. After being wounded, it heals itself. By what? By whom? The idea is forced upon me of a Principle, tireless and friendly, which unceasingly creates me on its own initiative.

My organs appeared and developed spontaneously. My mediate dualistic understanding appeared and developed spontaneously. Could not my immediate understanding, nondualistic, appear spontaneously? Zen replies affirmatively to this question. For Zen the normal spontaneous evolution of man results in satori. The Principle works unceasingly in me in the direction of the opening of satori (as this same Principle works in the bulb of the tulip towards the opening of its flower).... An old Zen master said: "What conceals Realization? Nothing but myself." I do not know that my essential wish—to escape from the dualistic illusion, generator of anguish—is in process of being realized in me by something other than my personal "me." I do not believe that I can count on anyone but myself: I believe myself therefore obliged to do something. I take fright in believing myself alone, abandoned by all; necessarily then I am uneasy and my agitation neutralizes by degrees the beneficial work of my deeper self. Zen expresses that in saying: "Not knowing how near the Truth is, people look for it far away ... what a pity!"

This manner of thwarting the profound spontaneous process of construction is the work of mechanical reflexes. It operates automatically when I am not disposed to have faith in my invisible Principle and in its liberating task. In other words, the profound spontaneous process of construction only makes progress in me in the degree in which I am disposed to have faith in my Principle and in the spontaneity, always actual, of its liberating activity....

My participation in the elaboration of my satori consists, then, in the activity of my faith; it consists in the conception of the idea, present and actual, that my supreme good is in process of being elaborated spontaneously.

One sees in what respects Zen is quietist and in what respects it is not. It is, when it says to us: "You do not have to liberate yourselves." But it is not in this sense that, if we do not have to work directly for our liberation, we have to collaborate in thinking effectively of the profound process which liberates us. For this thought is not by any means given to us automatically by nature. The outer world unceasingly conspires to make us believe that our true good resides in such and such a formal success which justifies all our agitations. The outer world distracts us, it steals our attention. An intense and patient labor of thought is necessary in order that we may collaborate with our liberating Principle.

Arrived at this degree of understanding, a snare awaits us. We run the risk of believing that we must refuse to give our attention to life....

We must proceed otherwise. At moments when outer and inner circumstances lend themselves to it we reflect upon the understanding of our spontaneous liberation, we think with force, and in the most concrete manner possible, of the unlimited prodigy which is in process of elaboration for us and which will some day resolve all our fears, all our covetousness. In such moments we seed and re-seed the field of our faith; we awaken little by little in ourselves this faith which was sleeping, and the hope and the love which accompany it. Then we turn back to living as usual. Because we have thought correctly for a moment a portion of our attention remains attached to this plane of thought, although this plane penetrates the depths of our being and is lost to sight....

In the measure in which this second subterranean attention develops we will perceive a less compelling interest in the world of phenomena; our fears and our covetousness will lose their keenness. We will be able to learn how to be discreet, non-active, towards our inner world and we will thus become able to realize this counsel of Zen: "Let go, leave things as they may be.... Be obedient to the nature of things and you are in accord with the Way."

~ Excerpted from Chapter 13, "Obedience to the Nature of Things," in The Supreme Doctrine: Psychological Studies in ZEN Thought, by Hubert Benoit, with an introduction by Aldous Huxley.

![]()

Humor ...Baseball philosophy from the noted linguist Yogi Berra that applies as well to spiritual work:

Hey Yogi, what time is it?

~ From www.bostonbaseball.com/whitesox/baseball_extras/yogi.html |

Reader Commentary ...

(We appreciate hearing from you.)

|

Sign up for our e-mail alert that will let you know when new issues are published. Contact the Forum for questions, comments or submissions. Want to help? Your donation of $5 or more will support the continuation of the Forum and other services that the TAT Foundation provides. TAT is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit educational organization and qualifies to receive tax-deductible contributions. Or, download this .pdf TAT Forum flyer and post it at coffee shops, bookstores, and other meeting places in your town, to let others know about the Forum. |

The whole world does its works and commits it errors: but few are the lovers who know the Beloved.

The whole world does its works and commits it errors: but few are the lovers who know the Beloved.